After Michigan became a state in 1837, its leaders looked for ways to encourage settlers to move into the state’s interior. They were inspired by the success of the Erie Canal, which had opened in 1825 in New York state and had brought many new residents from the eastern seaboard to the Great Lakes region via water. Michigan’s legislature envisioned a canal that would cross the Lower Peninsula, linking the eastern Great Lakes to Lake Michigan.

Lawmakers knew that a shorter water route from Detroit to Chicago would be an important economic benefit for the new state. At the time, sailing from Detroit to the Windy City meant taking the long way around the mitten, up the Huron coast, through the Straits of Mackinac, and down the Lake Michigan shore. The proposed canal would significantly shorten the time and distance needed to make the trip.

The project was called the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal, and it was planned to use the Clinton and Kalamazoo rivers, along with an engineered waterway, to create a 216-mile canal across the state. Ground was broken for the project at Mount Clemens in 1838, with Governor Stevens T. Mason turning the ceremonial first shovel of dirt.

It turned out that the project looked better on paper than it did in reality. By 1843, only sixteen miles of canal had been built and work had stopped near Rochester. Engineers found out how difficult it was to traverse the thickly-wooded terrain and rolling hills, which required a series of locks and dams to overcome the many changes of elevation. Meanwhile, as the canal had laboriously inched its way from Mount Clemens to Rochester, its financing had dried up and railroads had begun to cross the state, eclipsing the canal as a transportation method.

The state grew tired of continually doling out more money for a canal that was making little progress, so it stopped construction in 1843. Some sections of the canal that had been completed were navigable by small barges and boats and were used for a short while by area farmers. But with nobody to maintain it, the waterway fell into disrepair and parts were filled in. In 1895, the legislature formally abandoned the canal and returned the right-of-way to the adjacent landowners.

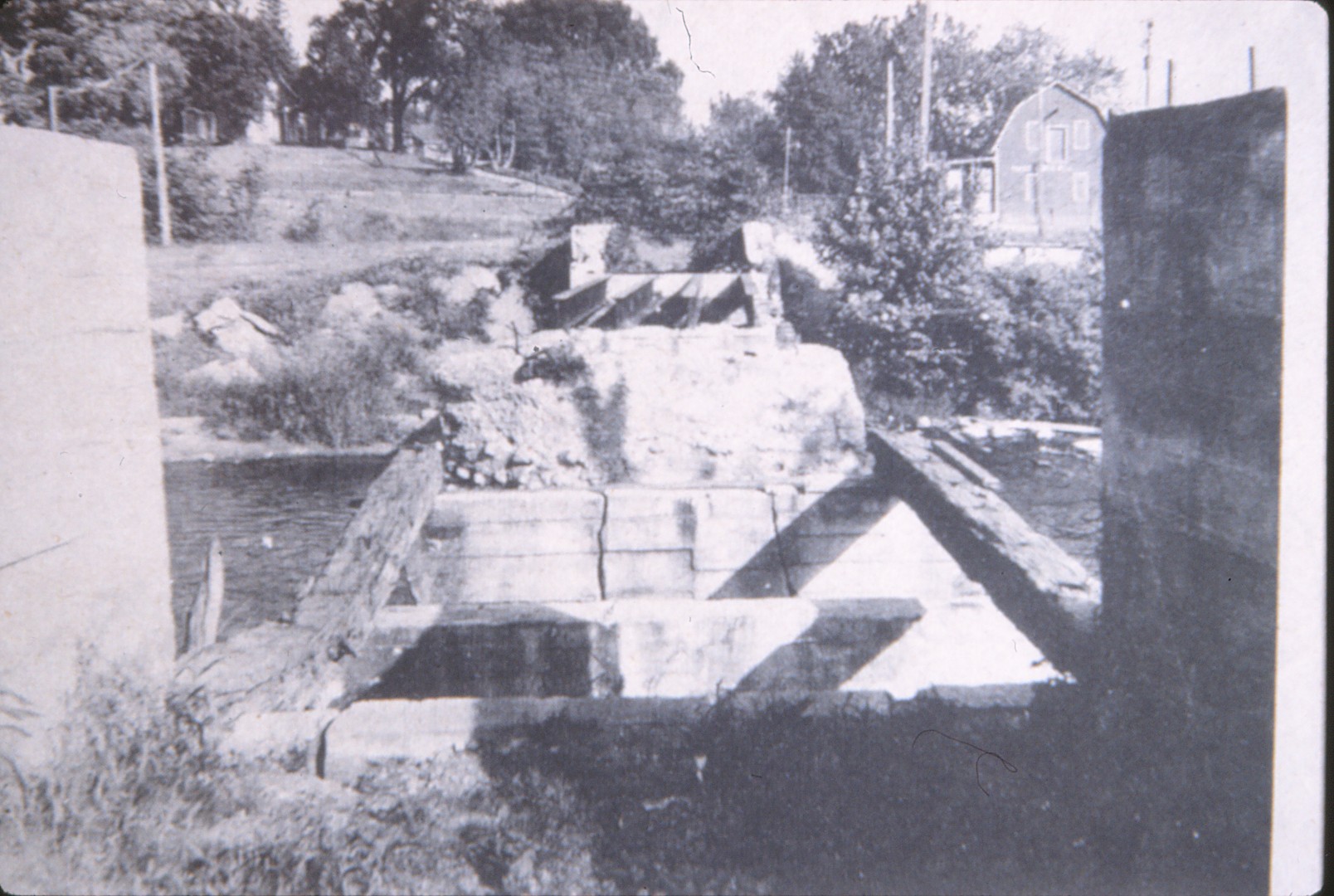

Although the precise spot where work stopped has not been identified, we do know that the canal construction reached the east side of the village of Rochester, near Yates, where an aqueduct had been built to carry the canal over the Clinton River. Over time, much of the canal was reclaimed by nature or was filled and built upon. Some remnants of the canal are visible in Yates and Bloomer parks in Rochester Hills, and other portions may be seen in Canal Park in Clinton Township. A Michigan Historical Marker stands in Yates Park, across from the cider mill, to commemorate the historic canal effort of bygone days.

Written by Deborah Larsen

Freelance writer, Copyeditor, Proofreader,

Research Committee chairperson with

Rochester Avon Historical Society.